I want to write more about Melancthon W. Janes today. Janes was born in 1841 in Crawford County, Pennsylvania. He moved, with his parents, Heman and Mariah M. (Rouse) Janes, to Erie Pennsylvania and was living there when the 1860 U. S. Census was taken.

I found a very interesting article about his father which I’d like to share with you. This article speaks to Heman Janes involvement in the early oil industry in Ohio—which is where Standard Oil had its beginnings.

Heman Janes Tarr Farm Producer

Feb 21, 2007 | Posted in Essays, People

By Neil McElwee

George Bissell, the majority investor in the land interest of the Drake Well, in November 1859 wrote to his wife in New York City about events reported to him and matters he observed first hand at the Drake Well site. He commented that in October, prior to a destructive derrick and pumphouse fire, the well was producing twelve hundred gallons of crude a day, or about 30 barrels a day. Though not impressive by todays standards, this Drake Well production was substantially higher than the average 12 barrels a day produced by the 100 or so producing wells in the early Oil Region in 1860. Production numbers jumped dramatically in 1861.

In the spring and summer of 1861, giant flowing wells of over 1,000 barrels a day first came in from the Oil Creek third sand at the small village of Funkville on the Lower McElheny Farm. Below Funkville on the Tarr Farm, a number of giants came in the fall of 1861 including the Phillips No. 2 at 4,000 barrels a day and the Woodford at 3,000 barrels. Several months before, realizing the significance of the third sand developments at Funkville, Heman Janes from Erie bought the entire Tarr Farm from James Tarr for $60,000. Records are incomplete, but writers of the time claim Janes soon after sold half the farm, the higher elevations, back to James Tarr. Surviving court records confirm the essence of the story. Heman Janes retained the portion of the farm close by the east bank of Oil Creek, the portion that contained the Phillips Lease and the Woodford Lease, his own wells and other big producers.

The Phillips Lease allowed for a royalty of one fourth with the provision the royalty crude would be packaged in barrels at the well, and the barrels would be provided by the working interest, the producer. When Phillips signed this very early lease with Tarr in November 1859, no one could foresee such huge production numbers or the inevitable consequence, a shortage of barrels. While the price of a barrel was quickly approaching $3 and the price of crude at the well dropping below 50 cents, Phillips and his partners notified the landowner they would not and could not package the royalty crude in barrels.

The landowner cried foul. He claimed this was a breach of contract and brought suit seeking damages of $112,000. The landowner was Heman Janes. The Phillips No.2 was shut down for several months until a settlement was reached. The settlement was a simple one; Janes royalty was increased from one fourth to a half.

Janes was an experienced businessman. While residing in Erie in 1858, Janes bought 200 acres of timber in Lambton County, Ontario. He bought the land not only for the timber but the oil-soaked gumbeds found on it. Shortly after, he leased another 400 acres of these beds soaked with sulfur-laden petroleum. However, the dramatic developments on Oil Creek turned his attention to Pennsylvania. Oil wells were eventually drilled on Janes Canadian property, which he sold in 1865 for $55,000.

In early 1861, Janes, Josiah Oakes, and General James Wadsworth, all from Erie, raised $300,000 to buy up the producing lands for ten miles along Oil Creek. This ambitious undertaking by Pennsylvania men came to an end when Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter in April 1861; the resulting panic hindered speculative ventures of all sorts. Janes sold all the oil property he owned in western Virginia. Janes and his Erie partners attempted another grand venture along Oil Creek in late 1861. They proposed a 4 in. pipeline made of wood be laid along the bank of Oil Creek from the Tarr Farm down to the mouth of Oil Creek at Oil City. The concept was to allow gravity to do its work and slowly but inevitably drop the crude in elevation over a run of about five miles. The concept may have worked since there would have been no need for pumps; the system would have been under a steady, low pressure from the natural head only. The partners made the mistake of seeking a charter from Pennsylvania. The local State Representative, M.C. Beebe of Pleasantville took exception saying he did not want to put 4,000 teamsters, his constituents, out of work. Beebe failed to mention the Oil Creek Railroad had begun construction from Corry on the Philadelphia and Erie to Titusville to capture what it could of the quickly growing crude oil market. Beebe used his influence to see to it Heman Janes early pipeline project would not be built.

While residing in the Village of Tarr Farm, a small back woods oil community Janes laid out and developed, Janes introduced the practice of casing wells. Prior to March 1865, the usual procedure in the Oil Region was to drill a 4 in. diameter hole in which a section of wrought iron pipe with a 2 in. inside diameter, in the field called tubing, was inserted. A standing ball valve and a sliding plunger with a ball valve were attached to the bottom end of this first section. Thin sucker rods that passed down the inside of the tubing actuated the plunger. The arrangement would lift, or pump, the crude to the surface. To reach the bottom of the well, sufficient sections of 2 in. tubing were added.

Below the level of invasive ground water, a flaxseed bag was securely tied around the outside wall of the tubing to create a water seal. Each time the tubing was pulled; the water seal was broken. The tubing was pulled often and for a variety of reasons including testing, a fouled pump, joint leaks, a torn flaxseed bag, and on. The best of operators would inevitably flood their wells with water. By 1864, the great Tarr Farm was shut down, completely flooded by ground water.

Throughout the balance of 1864, Heman Janes persuaded and cajoled a number of heard-headed producers with leases on the Tarr Farm to join with him and spend some money, pump the water out of their wells, pull the tubing, and redrill their holes to a diameter of 5 inches. The producers agreed and drilled wider holes. A flaxseed bag, or water seal, was permanently attached to the outside of a section of heavy wall wrought iron casing with an inside diameter of 3 inches. This section and additional sections were inserted down into the redrilled well to a depth sufficient to be below the infiltrating water above. The working 2 in. tubing was then inserted into the casing. The water seal, the flaxseed bag, attached to the outside wall of the casing remained fixed and undisturbed when the separate working tubing was subsequently pulled.

Heman Janes carefully planned program of recovery worked. After an expensive redrilling and casing program, the operators agreed to pump the wells in a synchronized fashion managed by Janes. By March 1865, the once dead Tarr Farm was pumping collectively 1,000 barrels a day.

This first use of casing was called wet-drilling. George Bissells Central Petroleum Co., the producing company that owned nearby Petroleum Centre, adopted this technique and synchronized pumping. The Columbia Oil Co. on the neighboring Story Farm did the same. By 1868, the Columbia Oil Co. superintendent reported he was drilling all new holes down to below the water infiltration level and then inserting casing with a fixed water seal. He then dry-drilled through the permanent casing down to the producing sand. Within a few short years, the more enlightened producers of Oil Creek had adopted the best of these efficient, productive oil field practices. Heman Janes is the producer early writers credit with being the man who showed them the way.

Heman Janes remained a resident of the Village of Tarr Farm until the latter 1870s. While residing at Tarr Farm, he invested heavily in the Bradford Field. Janes returned to Erie in 1878. The Village of Tarr Farm vanished in subsequent decades consumed by the returning woodlands growing about it.

References:

Sketches in Crude Oil, John J. McLaurin, Harrisburg, 1898

The American Petroleum Industry, The Age Of Illumination 1859-1899, Harold Williamson and Arnold Daum, Evanston, 1959

The Derricks Hand-Book of Petroleum Vol. I, P. C. Boyle, Oil City, 1898″

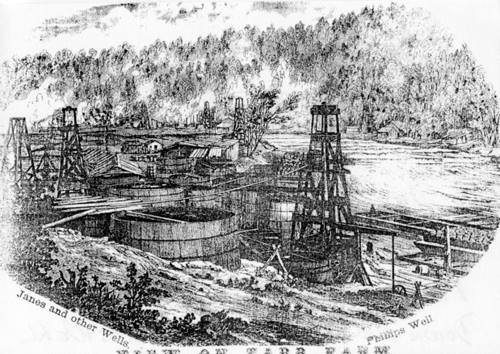

Photo 1 – a sketch of the Tar Farm Oil Field in 1868.

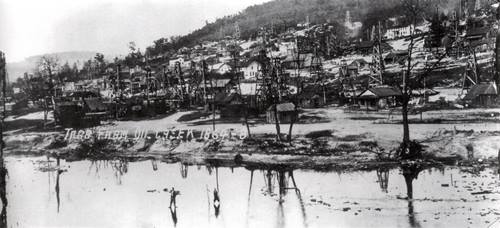

Photo 2 – a photograph of the village of Tar Farm in 1868

Photo 3 – A photograph of Tar Farm in 1990

Photo 4 – A photograph of the Heman Janes House in Erie, PA