From:

The Country Gentleman

Curtis Publishing Company

Volume 78 – #2

January 11, 1913

A BIG FARM THAT WASTES NOTHING

The Methods of a Man Who Knew How To Mind His Own Business.

Near the door of the fine old living room at the Adams ranch is a motto, the first thing noticed as you enter: The reason men who mind their own business succeed, is because they have so little competition.

Its a good thought, and you know that the man who bought the motto and hung it there, was a bit different from the average farmer. And H. G. Adams of Maple Hill, Kansas is a whole lot different, and so is his farm, and so are his cattle. You begin to hear about the man and his possessions as soon as you meet cattle buyers in the stockyards at Kansas City. You see his herds and you hear passersby talk about his four big concrete silos when you ride the train west from Topeka, and then you know, that over there at the right of the track, where you see a cluster of buildings, that seem to be a town, that there is an exceptional man that does things.

To the casual person, the successes of some men seem mysterious and out of reach. But they are not: the story of the rise of Horace Adams is commonplace enough. The influences, the conduct that made success possible for him, the conduct that made success possible for him, were and are within the compass of any American farmer or breeder. The motto in the living room are likely to show how the mans thoughts run: it indicates a spirit of independence of action. Every neighbor might be out-of-date in his methods of farming, every feeder might pursue a method that gave indifferent results, but through it all, Horace Adams was certain to go about his own business in the way he believed best. That was how he had won his prizes, his rewards. That was the dominant characteristic that any visitor would be sure to discover. The way things are done by a man like Horace Adams, is a way worth studying.

Prize Beeves on Poor Land

I dont see how you spend so little for machinery, said a neighbor. Youve had that mower ever since I was a youngster and cast my first ballot. Now one of those things wont last me more than a year or two. I dont understand it, your mower is no better than mine. I put my machine in the shed too.

A mower cant be worn out in a year or two, Mr. Adams declared. The frame and the tongue and other parts are made to last for a long, long, time. The trouble is, many men forget about the small parts that need to be replaced. A mower ought to last for fifteen years or more. I have several that have been in service longer than that. Our machinery is put into the sheds in the fall where the men oil and grease the parts. Broken parts are replaced. Nuts and bolts are tightened. The wooden parts are painted. By spring, the things are ready, every blade sharpened when the work is ready to begin. All this repairing and replacing can be done in the hours that would be idle time on many ranches and farms. We have no idle time here. Its all productive time.

A man with a worn out farm went to Mr. Adams a dozen years ago, discouraged. His land, broken from prairie sod, had been planted in corn for exactly forty-seven years. The yield had fallen to a trifle more than twenty-one bushels per acrethe yield of 1870 Kansas. He couldnt make things pan out any longer, both ends wouldnt meet, he was through.

It was a sorry looking farm that Mr. Adams bought in that deal, but he knew what he was getting. He knew how to put new gold into the mine that had been systematically robbed for nearly a half century. Its always the man who knows that gets ahead. Horace Adams put cattle yards over a part of his purchase, made pastures out of the remainder, and turned in a nice herd of Whitefaces to spend the winter there. After the land had been pretty well fertilized, alfalfa was planted there. The profitless acres began to thrive amazingly. Beeves that took all kinds of prizes and graced the Christmas tables of Kansas City, had tramped fertility into the soil again. The farm was worth many times the price he had paid.

Then came 1903, the year of the big flood in the Kaw Valley of Kansas. When this disaster had gone on about its business, Mr. Adams purchase was covered with a foot or more of fine, yellow, powdery sand hiding every blade of grass and every stem of alfalfa. Most men would have been discouraged. Horace Adams let things dry thoroughly and waited for windy days, and when they came, he send men with discs, stirred up the sand, and watched it depart for Nebraska and Colorado, and other parts unknown. It blew awayevery bit of it! When it was gone, the alfalfa was discovered alive and well and on the job, stems rotted mostly but when turned under they put nitrogen and humus back in the soil. Corn was planted the next spring and it exceeded the Biblical promise many fold for it provided the sower forty-two bushels per acre. The land once more was as good as it was the day it received its first seed back in the fifties. You couldnt buy it today for $250 per acre.

You cant make choice beef from common steers, Mr. Adams said not long ago. Good beef, well marbled beef, doesnt grow in common animals. It cant. Blood is the thing that counts.

With this idea in mind, it wasnt strange then, that Horace Adams found himself prepared to do so and promptly turned his attention to Hereford breeding and feeding. His father Alexander, and his brother Franklin had given much time to the acquiring of land and they owned much of it. This son put his earnings into the acquiring of full-blooded, unregistered Herefords. His farms having grown beyond his needs, he rented the land to tenants and took his share of the yield in payment. For his part, he bought the best bulls and kept his breeding pure.

After a while, the business at Maple Hill outgrew the ranch, he and the partner he had taken in, Mr. Roberts, bought ranch land in Meade County, Kansas. The X.I. Ranch covers 35,000 acres for which the two men have warrenty deeds and 30,000 acres of leased lands that extend far into Oklahoma, a great estate over which roam thousands of head of purebred Herefords, a few Shorthorns and some Angus. Four hundred acres along the Cimarron River is in alfalfa. After they have grown to proper feeding age on this mammoth property, the cattle are shipped, not driven as in the old days, to Maple Hill. There they are kept on pasture until March or April if possible, and the grass is excellent. No timber has been cut on Adams property, so there is plenty of natural shelter.

Conservation of Corncobs

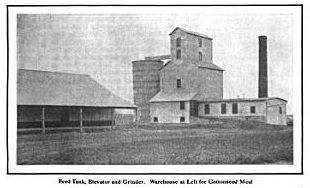

When finishing time comes, the wagons and the men are busy. The warehouses are opened and cottonseed meal is trundled out. The big silos, four in number, are brought into requisition. Those silos have already been described in The Country Gentleman so it will be enough to say that each is 60 tall and 30 across, are made of solid concrete, have 6 thick walls, and holds 50 tons. This means that a freight train of 60 cars would be required to carry the silage they hold. The beef-producing food that these silos contain, is the finest kind of insurance against drought. The ration for each Whiteface is forty pounds of silage, two or three pounds of cottonseed meal brought up from Oklahoma, with cottonseed hulls for additional ruffage. In the first crisp days of October, the cattle are allowed corn and cobmeal, ground in the big steam-powered grinder, rather than silage. With proper equipment, one man, it has been proved, can feed 1,000 cattle, serving the ration from a big wagon into feed boxes in the corrals. The Maple Hill ranch feeds about 5,000 head of cattle per year.

Of course a ranch of that size requires the best kind of equipment that can be procured. There isnt an old, worn-out idea on the Adams Ranch. Even the business office is equipped with up-to-date methods and simple equipment. It is not overladen with systems, blanks or reports but the books are kept by a Scotsman who knows how to do his work. The letters that are sent from this office are typewritten on stationery that gives the name of the ranch and its owner, a feature that many businesslike farmers and ranchers are adopting, and that all of them should adopt.

Mr. Adams clings to much of the old-time cattlemans generosity when it comes to the small details but he is certain of everything on the ranch-farm that it pays him to watch. He knows that it is good corn that passes over his scales on the way to the elevator. He knows that nothing is wasted, for the corn that enters his big monolithic grain tank at one side, emerges later after a journey up and round and down again, as the best of corn and cob meal to be made into Christmas beef. He knows that there isnt a great deal of nutriment in a corn cob, but it serves as good roughage if chopped fine enough.

Carloads of corn are stored in the concrete tank adjoining the elevator and grinding equipment. All this machinery is operated by steam, and an engineer is required, but this one engineer, on account of the various shafts and belts that he watches and keeps in order, saves the ranch thousands of dollars in labor. It doesnt take long to load feed wagons when they are stationed under a chute that drops the loads into them as fast as they can drive into place. Silage can be loaded into the wagons almost as quickly at the big silos, where wagons stand directly under a chute while men pitch the loads into them.

The story about Mr. Adams mower is understood when one sees his machinery shelter. It isnt large because Mr. Adams does not farm many acres, but all of the wagons, manure spreaders, cultivators, planters and other equipment are stored there for the winter and in perfect order. Nothing is seen lying around. A large supply of salt for the cattle is stored nearby in a concrete structure. The coal used for steam and heating is also stored in a concrete structure. The chickens have a concrete house facing the morning sun. The foundations of the sheds are concrete and so is the floor of the engine house at the elevator and grinder. Watering tanks for the Herefords are made of concrete and are kept filled by a dozen or more windmills, power always to be depended upon in Kansas. The feed boxes are wooden, but wont be for long, declares Mr. Adams, who will replace them with concrete.

In the beginning, Mr. Adams bought steers for seven or eight years and drove them up overland from the panhandle of Texas. He believes, too, that to this day that if driven slowly, and allowed to graze as they go, that they will do much better than in railroad boxcars. Not even the law requiring the uploading and feeding of cattle, will save them much loss, Mr. Adams says, because very often they are unloaded within thirty miles of their destination. If the legal period chances to expire thereand again go through the thinning ordeal of eating improper food and drinking poor water. Driven overland, in the fall, with good grazing, they should reach the feeding ranch in good shape and with their appetites keen for good meal and silage.

Studying the demands of the market, Mr. Adams learned years ago, that only the best beef could get the best prices. With the public asking for high class meat, it was wisdom to breed high class steers. The day of the Longhorn had passed. The population of the country was increasing amazingly, a meat-eating population that gobbled up a trainload of cattle in an hour. Instead of herds of half-fed, short grass stock, herds that sometimes straggled for miles along the Arkansas, it was necessary to produce smaller lots of better cattle, more carefully and scientifically fed. The country still needed thousands of cattle every twenty-four hours, but the cattle had to be of quality with real meat.

The breeder interested in making real money, will try to supply the steaks and ribs that the people crave. He knows that cheap cuts are no longer popular. He watches the calendar, too, and when the autumn crispness comes, his broad backed Herefords or Angus or Galloways or Shorthorns are contentedly munching their way closer to the fatal block, for Christmas brings a brisk demand for the best in keeping with the popular ideas of livingwhich may have something to do with the high costs of things in general.

Horace Adams, and his partner, Mr. Robert, gave their attention to supplying this trade. It paid for one member of the firm to be the breeder on the big ranch in the South, while the other did the feeding under the best of modern conditions. And it paid the feeder to have his farming done by tenants, on shares. This was and is the Adams system.

But it has not been all Herefords and money. There is a big, comfortable home in which the living room with its seven or eight easy chairs form a principle feature, a home from which no boy or girl goes out for a high school or college education without a yearning for the holidays and vacation.

No boy ever runs away from such a home, and yet it doesnt contain one thing that any American farmer might call a luxury. It is however, one example of what a farmer can do, far from a city, to have many of the comforts that are part of a city home. A pressure tank in the basement didnt cost much, but it supplies the entire home with running water and makes it as modern as a home in Chicagoand a lot more delightful. An acetylene light plant that lights the home certainly did not much injure the Adams bank account, and would be within the means of most farmers. The hot water furnace which heats the home could scarcely be called evidence of wealth, yet few farmers ever buy one.

The chief comfort, in this story of a big farm and ranch, lies in the fact that any intelligent farmer or breeder, can do just as Horace Adams has done. The power of good example is everywhere admitted. The wonder is that so few good examples have been copied.

For instance, the Adams place is held up to be a model in Kansas. Certainly no property in Kansas has more modern buildings or equipment. But scarcely one evidence of this kind is to be found in the surrounding Maple Hill Township.

For nearly a quarter of a century, the more advanced citizens of one community had talked about having a bridge across the Kansas River. Not very long ago the matter went to a vote. It was carried on one side of the river, but on the Adams side, it was defeatedand by the very farmers it would help the most. Adams, against advice of counsel, bought all of the bridge bonds that had been defeated, taking his chances of someday collecting their value. The bridge was built. You can drive along country roads near Maple Hill, over concrete culverts and little bridges built chiefly by this man that never would have been built had he objected. You can ride a stones throw from his boundary lines, in some cases, and find the same old tin or wooden structures.

In olden times, the tenants looked to the great house for never-failing support. It was the safe halve, the place where grain might be exchanged for coin of the realm, where there was always a friend. It isnt much different today on the Adams farm. There are tenants enough, goodness knows, for the owner, having turned his attention to Herefords and blue ribbons, finds profit enough in renting his lands to tenants, and having them give him half of all they grow. All day long, and sometimes into the night and until day break, lines of wagons laden with corn line up to pass through the corrugated iron passage way above the scales and on to the grinder and big scales. Some of those who raise this corn are tenants, some are farmers in their own right, but all of them, whether landlords or renters, look to the master of Maple Hill for their market.

##################

The three photographs below accompanied the magazine article.